This article was originally published in Spanish in Forbes México.

For the past few months, I’ve been on a mission: Convince Village Capital that we need to support financial inclusion entrepreneurs in the region, beyond just Mexico, and that we need to do it now.

In the past two years, alongside key partners like PayPal, BlackRock, and Autodesk Foundation, we’ve discovered impressive ventures across Latin America: Banlinea (Colombia), Huli (Costa Rica), ViperMed (Uruguay), Develop Link (Guatemala). Because each already had operations in Mexico, we were able to include them in our programs. But there were others, like Destácame (Chile), who didn’t yet have a country manager in Mexico, and were thus ineligible.

I, for one, have total FOMO.

To all the entrepreneurs outside Mexico: you don’t have to convince me that you’re out there. Great mappings exist for FinTech ventures in Colombia, Chile, and Argentina. And organizations like NXTP, Startup Bootcamp, BBVA Open Talent and Inclusión Plus, I see you, too.

But quality pipeline isn’t what’s holding us back. Before expanding our reach, we needed to know: Latin American founders: Are you “VC-investable” (attractive to a venture capital investor)? Do you have the capacity to scale and address the financial inclusion challenges that we care about?

What does it mean to be “VC-investable?”

At Village Capital, we evaluate companies’ investment-readiness on nine categories: team, problem and vision, value proposition, market validation, business model, product, product-market fit, scale, and exit potential. The big red question mark on our entry to new Latin American countries really focused on the last two categories: Can these entrepreneurs scale enough to be attractive to later-stage investors or acquirers?

For VC investors to profit, we need one of three things to happen: another investor commits capital after we do (usually north of $20 million dollars) in turn buying out the initial investor’s stake; a larger company acquires the startup; or the venture goes public in an IPO.

Makes sense. Venture capital investors want to make money. So, what’s the hang up?

Reality is, only a couple dozen venture capital investors in Latin America have ever experienced a profitable exit.

Beyond Mexico, there have still only been a few notable exits in the VC FinTech space in Spanish-speaking Latin America, when Caja Rural Los Andes (Peru) exited Elevar Equity’s portfolio, DineroMail (Argentina) exited from IFC, and Micropagos (Uruguay) exited from Tokai Ventures. (This is based on many direct conversations with investors and scouring the few lists that exist, including ALLVP’s Early Stage Active VCs in Mexico & Latam and LAVCA’s Latin America Venture Capital 5-Year Trends.)

The first challenge for entrepreneurs in most Latin American countries is reaching scale.

To be VC-investable, founders need to find a market with a lot of people eager to buy what they’re selling, so that the company can grow and eventually make more money than they’re spending to get new customers (even Uber with a global scale is still struggling to show it can turn a profit). If you start in a country like Chile, where the population is around 18 million–that’s less than the 21 million person population of greater Mexico City–and your product is only focused on a sub-segment of that population, your market is limited from the get-go.

As an extreme example in the region, Chile is tricky. When exploring the market there, I was told that one thing compounded entrepreneurs’ population size challenge: mindset.

Geographically, you have sea to your left, a long mountain range to your right, icy Patagonia below, and the smoldering hot desert up north. The challenge is that Chilean founders’ mindset all too often mimic these physical barriers, focusing on a local level, which isn’t dreaming big enough.

Even Startup Chile knows that entrepreneurs need to think beyond country borders if they want to scale and raise capital, and thus positions itself as the ideal platform for global ventures to land and attack the Latin American market.

Conversely, investors I spoke with almost unanimously agreed that Argentina had some of the best talent in the region and that the founders there understood that they needed to scale beyond country lines to grow a business. Startups like Despegar, MercadoLibre, OLX and Globant are all “unicorns” that scaled across the region and have been valued above $1 billion dollars!

Entrepreneurs, if you learn one thing reading this, it’s that we VCs need to know how you’re going to scale to exit if you’re going to seek our capital. I know you can. The examples are clear. But, so are the challenges, and we need to hear why your team is going to be able to do what so many others could not.

Your business has a vision for scale… But how will you make it to exit?

Across Latin America, venture capital is still a new thing. In many countries, investors are used to traditional “safe” investments like real estate, so the transition to earlier stage, riskier, mostly tech ventures requires cultural change. Many of the well-known VC investments have just been made in the past five years.

In part because the practice is so young, there are few reported VC exits across the continent and almost none in “real world” sectors like financial inclusion, health, education, agriculture, and energy. Investors know that funding startups is a gamble.

Many of the region’s top investors — like Ignia, ALLVP, Variv, IFC, and Kaszek — agree that it will take another five to ten years to build the case for exit opportunities in the region. Nevertheless, investors have hope in private equity and acquisition possibilities.

Entrepreneurs, if you’re reading this, here are the top two ways that investors in the region forecast that entrepreneurs can exit.

First: venture capital investors in Mexico agree that there is a trend for private equity companies to lower their investments to the US$10–20M range, making at least partial exits to larger firms a realistic pathway. For example, Kandeo Fund could be interested in $10M investments in FinTech. Private equity funds have a strong appetite for health investments, and ALLVP believes that this is a likely exit for their investments in clinics Médica Santa Carmen and Dentalia, as they reach a critical mass of branches.

There are examples of large Latin American corporations that acquired ventures within the region (most recently, BBVA Bancomer bank acquiring FinTech startup OpenPay and the holding company of microfinance institution Banco Compartamos, Gentera, purchasing Intermex). Latin American companies are still hesitant to acquire, but as a first step you are seeing corporate VC plays, like FEMSA investing in payments platform Conekta.

Alternatively, some investors believe that it’s more likely that American or European corporates will become the most active acquirers of Latin American ventures. For example, Fondeadora and Aventones were acquired by American and French companies, respectively. This is seen as the most likely exit opportunity for health and education ventures. Investors like LIV Capital have invested big in education (e.g. Centro, Mexico’s leading university focused on the creative industries). Based on their deep experience in education investments more broadly, they believe that exits can be achieved through any of the traditional routes: trade buyer, financial sponsor, recap, or IPO.

Additionally, some firms expect that US funds will come in and acquire a stake in FinTech ventures.

Bottom line, venture capital is all about taking measured risks.

After much contemplation, Village Capital has decided that now is the time to support Latin American entrepreneurs beyond just Mexico, starting with financial inclusion. And our global financial inclusion partner, PayPal, was also very interested in supporting entrepreneurs across LatAm so they are thrilled with this expansion.

We believe that we are best positioned to find and train the region’s entrepreneurs in having the necessary scale mindset to grow and thrive, starting with inviting entrepreneurs from three additional countries–Colombia, Chile, and Argentina–to apply to our upcoming FinTech program, which previously only included Mexico.

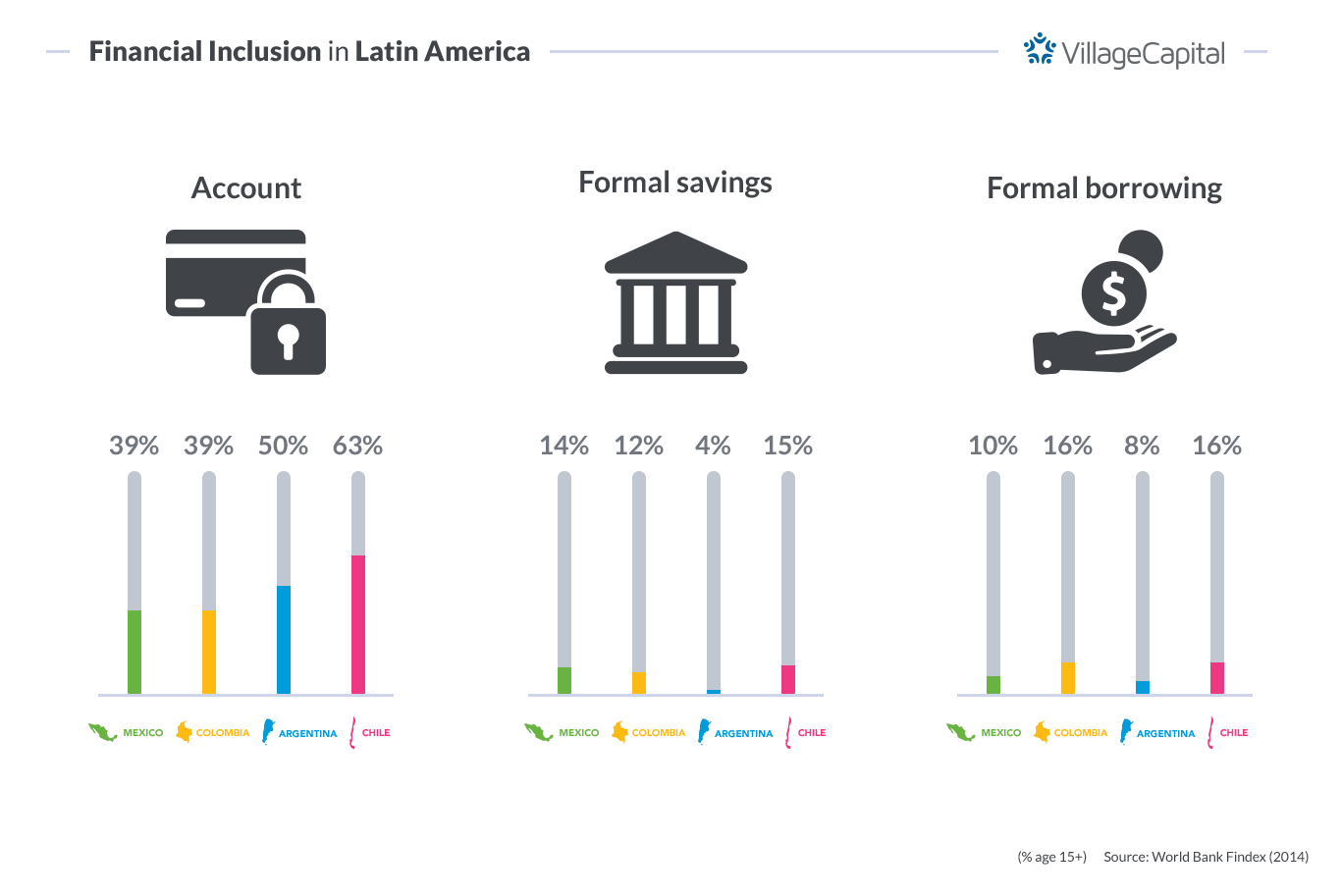

We not only believe that entrepreneurs in these countries have the potential to become VC-investable, but they also have the best vantage point to create huge impact on the region. In November 2015, we defined the FinTech challenges in Mexico specifically, noting that 61% of Mexicans don’t have a bank account, based on the World Bank Findex.

These stats are similar across the region with the four countries mentioned ranging 39–63% having bank accounts, 4–15% formal savings, and 8–16% formal borrowing. This is illustrated in the chart below.

We are already seeing lots of promising innovation. For example, mobile money has lots of potential in Latin America with ventures like our portfolio company ePesos pioneering in the sector. Furthermore, payments is one of the most active sub-sectors in FinTech in the region, providing investors with ample opportunities!

There are huge challenges to address in the region, but to investors like us, that means there is also a huge, untapped market opportunity.

Help me prove the VC community right. Applications for our next investment-readiness program, Village Capital FinTech: Latin America 2017, are open through through Friday, June 23. Apply today, or recommend an entrepreneur.

Let us help you build your path to scale, provide access to affordable financial services to individuals and small businesses across the region, and become one of Latin America’s first VC success stories.